As readers of this blog most likely know, I conduct research and teach at a university in Vancouver. Some will also know that I am a trained archivist, and that my field of research is archival studies. I’ve written before about the ways in which A’s death affected my studies as a PhD student and altered the nature of my research agenda. For several years now, I’ve been thinking about how grief and bereavement fit into my chosen field: how might a deeper understanding of the relationship between grief and recordkeeping impact archival thinking and practice? Grief is something archivists encounter pretty regularly; for example, a recently widowed donor might bring in her spouse’s records, or a residential schools survivor might comb records to find clues to what happened to her siblings or other family members. But archivists don’t really talk about grief – at least to each other – and there’s very little discussion about how having a better understanding of grief might help us to provide better services and care to the people who donate and use the records we preserve.

To address this gap (in part at least), I’m conducting a study that aims in part to fill that gap, to begin a conversation in the archival field about bereavement and recordkeeping, about emotion in the archives, and in particular, about grief in the archives. (You can read more about my work in this area here: https://blogs.ubc.ca/recordkeepinggriefwork/)

In my years of writing here and of working in other ways, too, to preserve A’s memory, I’ve thought a lot about how what I’m doing – in some ways – is building up an archive of my love for her and about how doing that work keeps me connected to her memory. I’m interested now in talking to other bereaved parents about their own experiences of grief and recordkeeping. Recordkeeping is a term archivists use to encompass making, using, organizing, and keeping records. A record can be anything a person makes, uses, or keeps to preserve evidence or memory; in this project, we define a record as any document or object that you make and/or keep to remember your baby. You might keep records just for yourself, or you might share them with others. You might keep some for a short while and others forever. Records can include things like photographs, ultrasound images, journals, letters, emails, blogs, hospital records, etc. They might also include objects like a stuffed animal, an item of clothing, a special rock or dried flowers, etc. Records might also include ephemeral items that are important to you because they are connected in some way to your baby or your memory of your baby. Essentially, for this project, anything you make or keep as part of your effort to perpetuate the memory of your child can count as a record.

If you’re reading this, and you’re a bereaved parent who has built, or is building up, a collection of records – of any type – related to your baby and/or to your experiences of bereavement, and if you are interested in learning more about this research project and about possibilities for participating, please send me an email at jen[dot]douglas[at]ubc[dot]ca. I’ll be happy to provide you with more information about the research objectives and methods and to answer any questions. Please also feel free to share this invitation with other bereaved parents you think might have an interest in the project and/or in participating.

I don’t want anyone to feel pressure to learn more or participate; this is 100% voluntary, and I understand it won’t be of interest to every bereaved parent to take part in this type of conversation or work.

Thanks, as always, for reading here and for helping to hold me up all these years. I often think I would never have finished my PhD, never made it into the academic position I now hold, without the support I have received from readers of this blog. I’m forever grateful for this community.

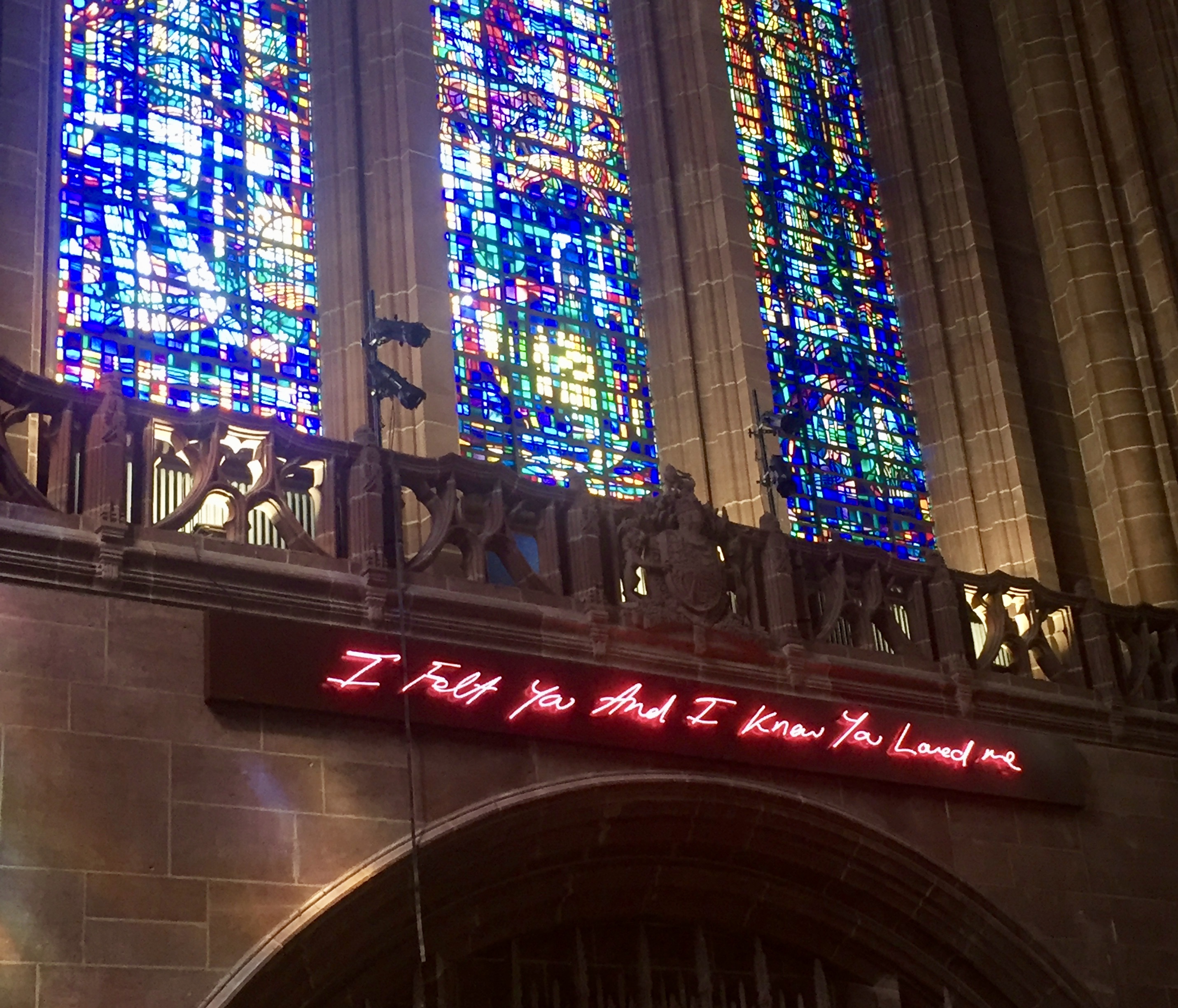

In the main part of the church, under a giant stained glass window, there was a message that felt like it was just for me, today.

In the main part of the church, under a giant stained glass window, there was a message that felt like it was just for me, today.  And then I visited the graveyard, trailed my hand along the tops of headstones and held in my heart the babies and the mothers who grieved them. I sat in the shade for a bit, waited, listened and then headed back to the conference.

And then I visited the graveyard, trailed my hand along the tops of headstones and held in my heart the babies and the mothers who grieved them. I sat in the shade for a bit, waited, listened and then headed back to the conference.

He stops to pick me buttercups on the way to school each morning. Splash of yellow clutched in his warm hand, the hand that will be caked in dirt when I pick him up after school from digging for lost villages at recess. His warm hand, still little, reaching out for mine while we look for the snake who basks in the long grass at the base of the big old fir, and his still-small voice asking question after question. Once, I so clearly imagined a future with two girls, sisters, and now I can’t imagine a present without him in it. The calculations never work out right; there’s never any real satisfaction in getting to the answer that doesn’t feel like a solution. But he is here and for as long as he is, I accept the buttercup offerings, tiny jars and cups of them all over my office and the kitchen table, and his warm, grubby hand and sweet, curious voice as we walk at the edge of the forest, still dark and cool on these early summer mornings.

He stops to pick me buttercups on the way to school each morning. Splash of yellow clutched in his warm hand, the hand that will be caked in dirt when I pick him up after school from digging for lost villages at recess. His warm hand, still little, reaching out for mine while we look for the snake who basks in the long grass at the base of the big old fir, and his still-small voice asking question after question. Once, I so clearly imagined a future with two girls, sisters, and now I can’t imagine a present without him in it. The calculations never work out right; there’s never any real satisfaction in getting to the answer that doesn’t feel like a solution. But he is here and for as long as he is, I accept the buttercup offerings, tiny jars and cups of them all over my office and the kitchen table, and his warm, grubby hand and sweet, curious voice as we walk at the edge of the forest, still dark and cool on these early summer mornings.